Adding trees to farms can help increase farm income, help mitigate climate change, increase biodiversity, and protect water sources

In Iowa, farms growing corn and soybeans dominate the state, but one farm in the southeast corner of the state stands out—literally. Red Fern Farm grows trees—chestnut, pawpaw, black walnut, persimmons, heart nut, and Asian pear.

Red Fern Farm, which is owned by Tom Wahl and Kathy Dice, practices agroforestry, which the U.S. Department of Agriculture defines as “the intentional combination of agriculture and forestry to create productive and sustainable land use practices.”

Jacob Grace, communications manager at the Savanna Institute, which is encouraging the adoption of agroforestry in the U.S. Midwest, says: “Agroforestry is trees on farms on purpose.” Further, he says it is one of the world’s oldest forms of agriculture.

Many farmers plant trees on their farms to create a windbreak, which could be the first step into agroforestry.

“A lot of people start with windbreaks and then realize, ‘we could be planting trees that also produce nuts or fruit, or produce leaves that my livestock can eat,’ ” Grace says.

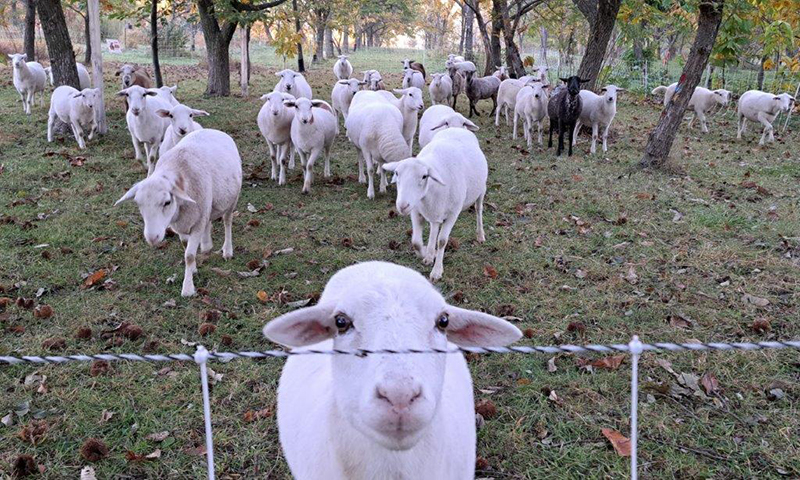

Sheep graze among the trees at Red Fern Farm

Two common agroforestry practices are alley cropping and silvopasture. Alley cropping involves incorporating trees into a row crop system such as corn or soybean production. Trees would be planted in an alternate row, such as every 10th or 20th row of corn or soybeans. Alley cropping can also be done with vegetable plants or fruit bushes.

Farmers can diversity their production and earn income from trees such as chestnuts or black walnuts or vegetable plants planted in an alley crop.

“The ultimate goal is to be raising an agroforestry crop that you’re harvesting and selling something from it, whether it’s nuts, berries, forage or something like that,” Grace says.

Red Fern Farm grows a wide diversity of trees on its 88 acres. “If it can grow in Iowa, we’ve at least tried to grow it on our farm,” Tom Wahl says.

Red Fern earns its income as a “u-pick” farm from its trees and fruit bushes such as aronia berry and cornelian cherry.

Silvopasture involves incorporating agroforestry into livestock production. Trees can be planted into a pasture, where livestock are grazing. As the trees grow larger, they can provide shade to the livestock. If trees are already present, farmers can add forage plants that livestock can graze on.

Red Fern Farm grazes sheep to cut grasses that grow near the trees instead of using mowers.

“The benefits of alley cropping and silvopasture are that you don’t have to take land out of production to plant the trees,” Grace says. “You can keep using it the way you’ve been using it while the trees get started.”

Climate mitigation, biodiversity, water quality

Agroforestry provides significant environmental benefits, according to Nate Lawrence, Savanna Institute’s ecosystem scientist. These cover three areas: climate mitigation, biodiversity, and water quality.

“With climate mitigation, agroforestry has tremendous potential to add a lot of carbon to the landscape,” Lawrence says.

Trees can sequester significantly more carbon per acre than regeneratively managed soils, possibly as much as 5-10 times more. Trees can store more carbon because of their size and increased biomass.

“We’re looking at multiple tons of CO2 per acre per year when we add trees to the landscape,” Lawrence says. This is compared to only fractions of a ton of CO2 per acre, per year sequestered in the soil.

Savannah Institute’s Illinois demonstration farm which has trees growing between rows of corn.

At Red Fern Farm, “these trees are grabbing carbon out of the air, putting it into their limbs, their trunks, and their roots,” says Kathy Dice. “Our system is absorbing a great deal of carbon.”

Biodiversity is another major ecosystem service provided by agroforestry. Biodiversity, which includes wildlife like insects and birds, has declined in agricultural landscapes due to monoculture crops such as corn and soybeans and synthetic pesticides.

“We believe that adding more vegetative diversity under the landscape, will help to reverse that decline and may actually help increase biodiversity,” Lawrence says.

The Savanna Institute is conducting research to measure the increase in biodiversity produced by agroforestry.

Kathy Dice has seen that increase in biodiversity among the trees at Red Fern Farm. “It’s an excellent wildlife habitat,” she says. “We have a lot of birds and pollinators, insects, snakes, and other reptiles out there.”

Water quality is a key benefit of agroforestry, particularly needed in Midwest states, which are experiencing water quality problems due to runoff of synthetic fertilizers from farm fields.

Agroforestry with its perennial trees that have deep roots could be effective at absorbing that runoff and preventing it from flowing into water sources.

“Then what comes in is more effectively held onto, cycled, and returned to food products that get harvested,” Lawrence says.

Agroforestry can also increase water infiltration into the soil from rain. “The water can actually soak into our ground,” Dice says. “The tree roots and ground cover roots help the water infiltrate and increase in the soil.”

Agroforestry as regenerative agriculture

With those environmental benefits, Grace says agroforestry qualifies as a regenerative agriculture practice.

“When it’s well managed agroforestry will absolutely improve soil health,” he says. “Agroforestry checks all the boxes with keeping the soil covered and keeping living roots in the ground. Agroforestry often incorporates livestock and diverse crop species.”

Red Fern Farms has continuous living ground cover. “There’s no bare soil in what we’re growing in between the trees,” Dice says.

The Savanna Institute gets its name from the ecosystem that existed in the upper Midwest before European settlers arrived, which was primarily oak savanna. The Savanna Institute is rooted in that legacy, says Grace.

“That’s some of the inspiration for the agroforestry work that we do,” he says. “How can we develop farming systems that look like and function like the ecosystem that was here originally with that productive savannah ecosystem of trees? We are using that native landscape as an inspiration for what we’re working for on our farmland.”

The goal of the Savanna Institute is to make agroforestry the norm and not “this special thing that needs to get explained,” Grace says. “We would love to reach a point where we don’t call it agroforestry anymore, we just call it farming.”