In March, the Iowa landscape—along with much of the upper Midwest—looks barren with vast fields of cornstalk stubble and brown soil left exposed from the previous year’s harvest of corn and soybeans. But in Winfield, Iowa, the fields of Jeff Olson’s farm are green with crops like cereal rye, alfalfa, and barley and pushing through the warming soil.

“My whole farm is green in March. It’s a picture of living soil,” Olson says. “The cover crops help keep the ground active all year round. The roots are building, and there is activity in the soil.”

Olson, along with a growing number of other Midwest farmers, is growing cover crops like cereal rye, alfalfa, clover, rapeseed, and others. Instead of leaving fields barren after the fall harvest, which can lead to soil erosion, more farmers plant cover crops in the fall and let them grow to spring, keeping roots in the ground year-round. Cover crops provides a range of benefits from preventing soil erosion and improving water quality to reducing chemical inputs and building healthier soils that can mitigate climate change.

Fastest-growing trend in U.S. agriculture

“Growing cover crops may be the biggest thing going on in conventional agriculture in the Upper Midwest,” says Mac Ehrhardt, co-owner of Minnesota-based Albert Lea Seed.

Anna Morrow, program manager, at the Midwest Cover Crops Council (MCCC), which supports cover crop production, agrees.

“Interest in cover crops seems to steadily growing even with lower commodity corn and soybean prices,” she says. “Farmers are seeing the benefits and growing cover crops, and it has become more mainstream.”

Cover crops were grown on more than 700,000 acres in Iowa in 2017, according to Sarah Carlson, Midwest cover crop director at Practical Farmers of Iowa (PFI), which spearheads efforts to convince farmers to grow cover crops.

“Ten years ago, there were 25,000 to 50,000 acres. We are seeing good growth but we need a lot more than 3 percent of 23 million acres of corn and soybean grown in Iowa to make that production sustainable,” she says.

Cover crop acreage in Illinois is also three percent of corn and soybean farmland; Indiana is a little higher at seven percent, according a report by the Environmental Working Group and PFI.

One of the main benefits of cover crops is preventing nitrogen fertilizers from running off farms and into waterways. Each year such runoff creates a massive “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico that kills fish and marine life. With roots in the ground all year, cover crops hold soil in place, keep nutrients in the field, and scavenge residual nitrogen before it leaches into waterways.

“The goal of cover crops is to prevent erosion, retain soil nutrients, and build soil health and biological activity. Managed correctly they can also control weeds and, in some cases, reduce insect pressure,” Ehrhardt says.

Protective armor for the soil

Cover crops act as a protective “armor” for the soil, says Gabe Brown, owner of Brown’s Ranch in North Dakota, and a leader in the regenerative agriculture movement

“We should never see bare soil because that’s not how nature functions,” he says. “Weeds grow because they’re trying to cover the soil. If you don’t have armor or (crop) residue on the soil surface, then you are prone to wind erosion, water erosion, and evaporation.”

“Keeping a living crop in the soil helps build organic matter,” Morrow says. “It helps with water infiltration; more of the rain gets into the soil instead of running off.”

More soil organic matter improves soil health, which can lead to increased crop yields. A 2015 Conservation Technology Information Center survey of more than 1,200 U.S. farmers found that cover crops boosted corn yields by an average of 3.66 bushels per acre and soybeans by an average of 2.19 bushels per acre.

Jeff Olson saw increased soybean yields after planting a cover crop before soybeans.

“In the fields where I planted rye as a cover crop there was a three or four bushel per acre yield increase. I found there was something that is good for soil,” he says.

Cover crops may also reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. Brown says he uses an herbicide only once every two to three years and hasn’t used insecticides or fungicides since the late 1990s. But Morrow cautions that “farmers have to build soil health, get nutrient cycling, and get the system down before they can get to those things. We hope that plays a role long-term.”

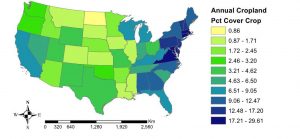

Cover crop production in the U.S. as a percentage of total crops in each state

Looking at the big picture, cover crops can also help mitigate climate change. Agriculture, particularly with its practice of tillage or plowing, depletes carbon in the soil and releases it into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change. A study conducted at Penn State University found that cover crops help soils sequester carbon, keeping it in the ground.

“We have way too much carbon in the atmosphere and need that carbon back down in the soil to feed soil biology,” Brown says. “Regenerative practices like cover crops help take that carbon out of the atmosphere and pump more into the soil.”

Cover cropping also complements no-till farming, which Brown and a growing number of farmers practice to keep soils undisturbed with no plowing or tilling.

Many different cover crops

Cereal rye is the most widely used cover crop in the Upper Midwest. It can be planted as late as November, survives winter, and comes up in the spring. It is often grown before soybeans. Cereal rye has an extensive soil-holding root system and helps to reduce nitrate leaching and suppress weeds.

Other common cover crops include oats, sorghum sudangrass, clover, alfalfa, peas, rapeseed, turnips, and tillage radish, among others. Crops like cereal rye and oats build soil organic matter. Clover, alfalfa and peas help to add nitrogen to the soil. Tillage radish helps to break up compacted soils.

Brown uses as many as 70 different cover crops on his farm.

Olson says he plants a lot of cereal rye. Of the 1300 acres that he farms, Olson says that one-half of that is planted with cover crops. Interestingly, he grows GM, non-GMO, and organic crops.

An engineering graduate of Iowa State University, Olson describes himself as an “experimenter,” trying different cover crops like turnips, radishes and rapeseed and admits “there is a lot to learn.”

More education programs needed

With the proven benefits of cover crops, why aren’t more farmers growing them?

It’s a new practice, says Morrow. “It’s going to change a lot of things you do on your farm. It’s a new thing that a lot of farmers haven’t worked with before.”

Carlson cites a lack of knowledge. “If they don’t know PFI or don’t have access to a neighbor who has done it, they may make mistakes.”

Fortunately, there are many education resources available from PFI, MCCC, Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE), and agricultural universities. MCCC has an online state-by-state cover crop selector tool that helps farmers choose cover crops that are best for their area. Carlson says many agriculture groups, conventional and organic, are offering cover crop educational programs.

One of the best things about cover crops is that they are embraced by all aspects of agriculture, from conventional and GMO farmers to organic growers.

Gabe Brown, who speaks to many groups about cover crops and regenerative agriculture, says that interest in cover crops is “unbelievable” and rightly so.

“They are a slam-dunk, no-brainer if you’re concerned about profitability, the health of your farm, and ecosystem. I can’t imagine why anyone would not plant cover crops.”