Ancient farming strategy holds promise for climate resilience

Published: February 6, 2023

Category: Regenerative Agriculture

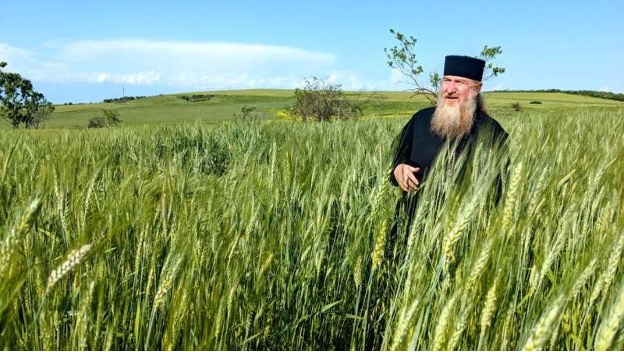

Nikoloz Lomsadze, senior pastor of a church in Dedoflis Tskaro, in eastern Republic of Georgia, looks over his field of mixed barley and wheat. He uses the mixture to make holy sacrament and church feasts.

Credit: Alex McAlvay/New York Botanical Garden

by Susan Kelley, Cornell University

Morgan Ruelle was living in the remote mountains of Ethiopia in 2011, researching his dissertation on food diversity, when he kept hearing about a crop that confused him.

The farmers repeatedly mentioned a grain called “duragna” in Amharic that had no equivalent in English. “They kept saying, ‘Well, it’s not really wheat, it’s not really barley,’” Ruelle says. “I was just kind of stumped by it for several weeks.”

Eventually a farmer explained that duragna was actually a mix of both wheat and barley, and sometimes other grains too, planted together, rather than one type of grain sown in orderly rows.

He had stumbled upon one of the few places in the world where farmers still sow maslins, or cereal species mixtures, which can contain rice, millet, wheat, rye, barley, triticale, emmer, and more.

The knowledge the farmers shared with Ruelle led to a paper by current and former Cornell researchers that suggests maslins, which have fed humans for millennia but now are largely forgotten, have the unique capacity to adapt in real time to increasingly unpredictable and extreme weather caused by climate change.

The research braids together previous work in agronomy, ethnography, archeology, history, and ecology. It shows maslins—from a Latin word for “mixed”—have been used for more than 3,000 years and in at least 27 countries, from northern Africa to Europe and Asia and later North America. Wild maslins may have even given rise to agriculture.

“Subsistence farmers around the world have been managing and mitigating risk on their farms for thousands and thousands of years and have developed these locally adapted strategies to do that,” says former Cornell postdoctoral researcher Alex McAlvay, the paper’s first author and now a researcher at the New York Botanical Garden. “There’s a lot we could learn from them, especially now, in a time of climate change.”

The practice continues today in Eritrea, India, Georgia, Greece, and Ethiopia. In Sudan, farmers grow a mix of rice and sorghum in areas that flood predictably; rice grows in flooded zones and sorghum grows under drier conditions.

In addition to its climate-adaptation benefits, maslins can produce greater and more stable yields, are more tolerant of drought, and better resist pests and weeds, when compared to single crops.

A mix of Eritrean wheat and barley outperformed sole-cropped wheat and barley by 20% and 11% respectively and yielded a higher quantity of flour per unit compared to pure barley in a field trial.

A farmer in Ambasel District, Amhara, Ethiopia holds a mixture of wheat and barley varieties harvested from his field. Locally, this mixture is called “megamegu.” Credit: Alex McAlvay/New York Botanical Garden

Compared with monocultures, maslins may produce more biomass—and take up more carbon than monocultures—because they tap into different nutrients and levels in the soil.

“What’s exciting to me is wheat is the third-most grown crop in the world, millions of hectares,” McAlvay says. “If you converted a large swath of what is just wheat into wheat and barley, you could actually make a difference.”

The findings are published in the journal Agronomy for Sustainable Development.

Source: PHYS.org

To view source article, visit:

https://phys.org/news/2023-01-ancient-farming-strategy-climate-resilience.html

Organic & Non-GMO Insights, February 2023