Organic farmers describe challenges dealing with herbicide drift

Drift from herbicides such as glyphosate and dicamba damages organic farms, and much more needs to be done to compensate farmers for their losses. This was the key message of an educational session at the Midwest Organic Sustainable Education Services (MOSES) Organic Farming Conference in February.

Suffered drift damage six times in eight years

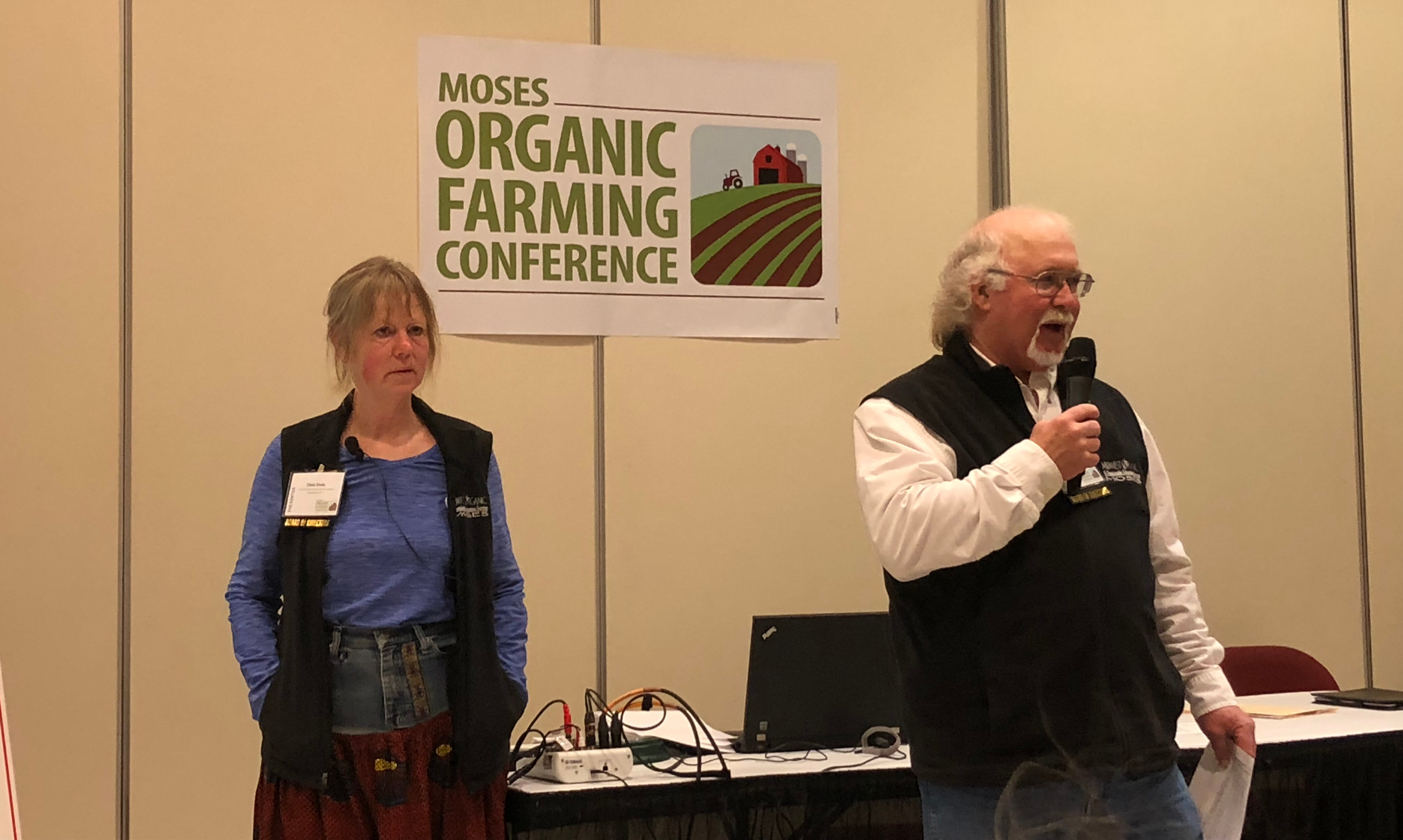

Charlie Johnson, owner of Johnson Farm in Madison, South Dakota and Dela Ends, owner of Scotch Hill Farm in Broadhead, Wisconsin described how herbicides sprayed on neighboring conventional farms drifted by air to their farms, damaging their crops and causing losses of income and organic certification.

“Herbicide drift is both vandalism and trespass, no doubt about it,” Johnson said. “It’s an imperfect science if you can’t keep your bull on your side of the fence. It should be the same for herbicide drift.”

Johnson, who grows corn, soybeans, oats and other crops on his 2500-acre farm, said his farm was damaged by herbicide drift six times in the past eight years. Five drift incidents involved glyphosate, the main ingredient in Monsanto’s controversial Roundup herbicide; the other was caused by dicamba herbicide, which is now being widely used because weeds are becoming resistant to glyphosate.

Johnson showed a photo of his organic corn and said “It’s a shame when a field like that can be damaged by someone’s use of chemicals.”

The number of acres damaged by drift on Johnson’s farm ranged from 5 to 60 acres, and he had to transition those acres back to organic.

Fortunately, Johnson was able to trace the sources of all but one of the drift incidents, and he was compensated for the glyphosate damage by either the herbicide applicator or an insurance company.

But he wasn’t able to trace the source of the dicamba drift in 2017, which damaged 60 acres of his organic soybeans.

“I don’t know where it came from, aerial or ground (spraying), and couldn’t find anybody who did the spraying,” said Johnson, who wasn’t compensated for the dicamba damage.

Not being able to trace the source of dicamba drift is another one of the many problems with the herbicide, which damaged an estimated 4.6 million acres of farmland in 2017 and 2018.

“The South Dakota Department of Agriculture was overwhelmed with 400 to 500 claims of dicamba drift damage,” Johnson said.

“I have to pray that nothing else gets blasted”

Scotch Hill Farm is a community supported agriculture program, producing vegetables, herbs, flowers, some fruits, hay, and small grains. In 2012, glyphosate damaged the farm’s snow peas, chard, and several brassicas. In 2013, Ends said her summer squash was “completely destroyed” by glyphosate.

“I’m not a bad farmer; my neighbors spray,”she said. “We can’t see the spray, and if it smells, it’s trespass.”

Ends’ farm is small at just 30 acres, making her crops especially vulnerable to drift. “We are a postage stamp in a sea of corn and soybeans,” she said.

Unlike Johnson, Ends was not able to receive compensation for the drift damage. The Wisconsin Department of Agriculture investigated her drift incident in 2012 and filed a report nine months later. An attorney told her it would have been a waste of time and money to take her complaint to court.

“It’s unfair,” she said. “I have to pray that nothing else gets blasted. We can’t even breathe the air. These are dangerous chemicals. We don’t use them but we have to fight them.”

What can organic farmers do to deal with pesticide drift? Johnson recommends documenting incidents and reporting them to the state department of agriculture.

“Keep records of what you smell and when you see applicators, everything should be documented,” he said. “This will help ensure you are taken more seriously.”

He also recommends putting up “no spray” signs on organic land and registering with DriftWatch, a voluntary communication tool that enables farmers and pesticide applicators to work together to protect specialty and organic crops.

But much more needs to be done. “We need policy changes, stronger liability laws, and an indemnity fund to compensate farmers (who suffer drift damage),” Johnson said. “The laws regarding agricultural chemicals need to protect people, land, and water, not corporate profit. You have the right to farm organically.”