Small mills investing in infrastructure revive local grain markets.

The sight of a truck loaded with Iowa-grown grain preparing for a long road trip west felt backward to Breadtopia’s Vice President, Galen Saturley. The grain had been grown practically in their backyard, but without a nearby cleaner that could meet their standards, it had to take a detour across the Plains before it ever reached their mill.

Galen described the situation plainly. “There wasn’t equipment around here that we could use, and there wasn’t anybody who could clean grain to the standard we needed,” he said. “So the growers that had great grain were shipping it to South Dakota to get cleaned and then shipping it back.” The inefficiency was so extreme that Breadtopia ended up sourcing much of its grain already cleaned, often from hundreds of miles away, even though the company sits in one of the most productive farming areas in the country.

The contradiction never stopped bothering him. “This is southeast Iowa. There are farmers everywhere,” Saturley said. “We wanted to buy from them. We just couldn’t.” The issue was the missing middle. Without a local cleaner, even growers excited about small grains, specialty wheat, or regenerative practices faced barriers that pushed them back toward commodity channels. The shipping alone cut deeply into their margins. “They’re spending so much money shipping their own grain to a facility and then shipping it back,” he said. “Then they’re making a lot less money on the grain, so they’re not as incentivized to grow grain for us.”

Breadtopia’s team realized that if they wanted a regional grain market, they had to build the link that no longer existed. The company invested its own capital into a compact but capable grain cleaning operation that now sits just a few steps from its milling and packing line. Saturley described the decision as both practical and phi losophical. “This is all a self-funded business investment,” he said. “We truly believe in the cause of it, and so we decided to put our own money into that.”

losophical. “This is all a self-funded business investment,” he said. “We truly believe in the cause of it, and so we decided to put our own money into that.”

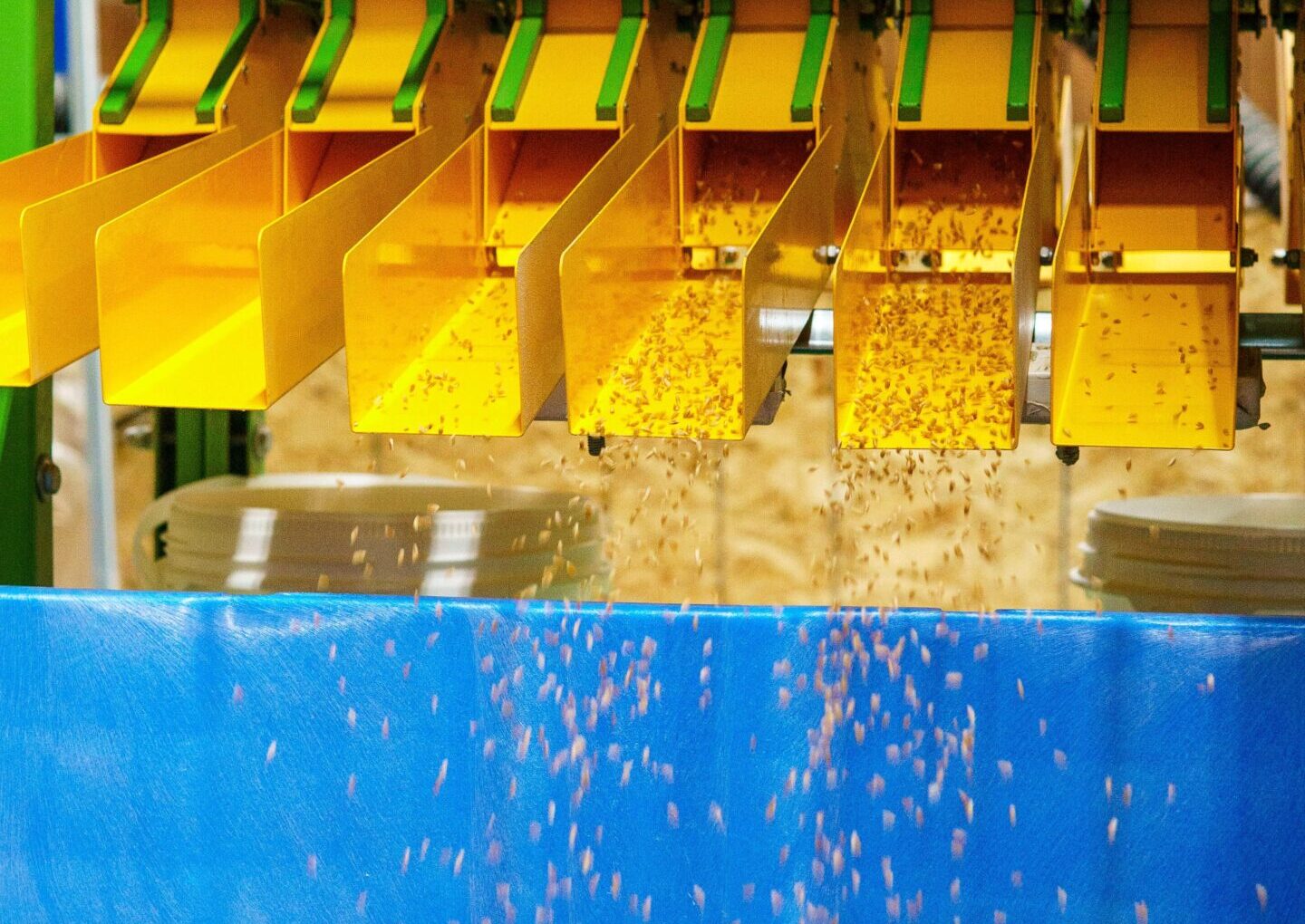

The buildout took months of research. Saturley consulted farmers, co-ops, and other operators to understand what combination of equipment could handle the varieties and conditions Breadtopia works with. He eventually assembled a line that includes an aspirator, a dehuller for hull-on grains like einkorn, and an optical sorter that identifies off-color kernels and damaged grain with remarkable precision. “The optical sorter is the one that I plug in the parameters of what we’re keeping and what we’re not keeping,” he explained. “By using the cameras, it tells the jets to separate into channels.”

The technology is essential, but the bigger shift is what the equipment makes possible. “With not having that cleaning equipment locally, farmers have fewer opportunities to grow grain in the ways they want to grow it,” Saturley said. The new facility removes that barrier. Growers can bring in grain that is certified organic, or grain grown according to strict practices but not yet certified, and Breadtopia can clean, mill, and sell it. “It basically allows for a market for grain that is properly grown or has best practices of organic, but is not necessarily certified,” he said. “We have the option to clean it, to mill it, and to try to find a marketplace for it.” That flexibility matters for producers experimenting with new varieties or transitioning to organic systems. Many are working to rebuild crop rotations that include small grains, yet they have lacked a predictable market.

The move also aligns with shifting consumer behavior. Saturley has watched interest in home milling rise steadily. “People are milling fresh flour at home,” he said. “You can essentially source your grain within probably ten miles of where you live.” That trend rewards mills that can connect directly to nearby growers and provide flour rooted in place and practice. Their grain now comes from fields close enough for the grower to drop off a load in the same afternoon.

Breadtopia’s cleaning line is intentionally small. Saturley calls it a seed-stage investment, designed to support the immediate local network and grow only as that network expands. “Small,” he said without hesitation when asked how he would classify its size. The company’s long-term vision is not to become a dominant processor but to model what is possible. “We are hoping to be a prototype for other small communities,” he said. “If we can figure out a way, then we are happy to expand that knowledge and operation to other communities. It doesn’t have to be our name. It doesn’t have to be our business.”

Across the country, other communities are confronting the same bottleneck Breadtopia solved. Small grains, organic rotations, regenerative systems, and local milling all require the same foundational piece of infrastructure. When a region lacks a cleaner, the entire system collapses back into long-distance hauling and commodity pricing. When a region builds one, even at a small scale, the economics shift immediately for farmers, bakers, brewers, and local buyers.

Saturley believes that any rural community with growers interested in specialty grains or regenerative practices could replicate the model. The scale does not need to be large, and the investment does not need to be corporate in nature. The equipment is the means to more markets, but the impact grows from the relationships it enables.

Saturley believes that any rural community with growers interested in specialty grains or regenerative practices could replicate the model. The scale does not need to be large, and the investment does not need to be corporate in nature. The equipment is the means to more markets, but the impact grows from the relationships it enables.

The company’s willingness to take on the role of cleaner, processor, and market fills a structural gap that many rural regions face. The disappearance of mid-scale mills over the last century left farmers with a choice between hyperlocal direct sales or the commodity system, with very little in between. Saturley summed up the company’s approach simply. “We’re not trying to take over the world,” he said. “We’re just trying to improve it.”