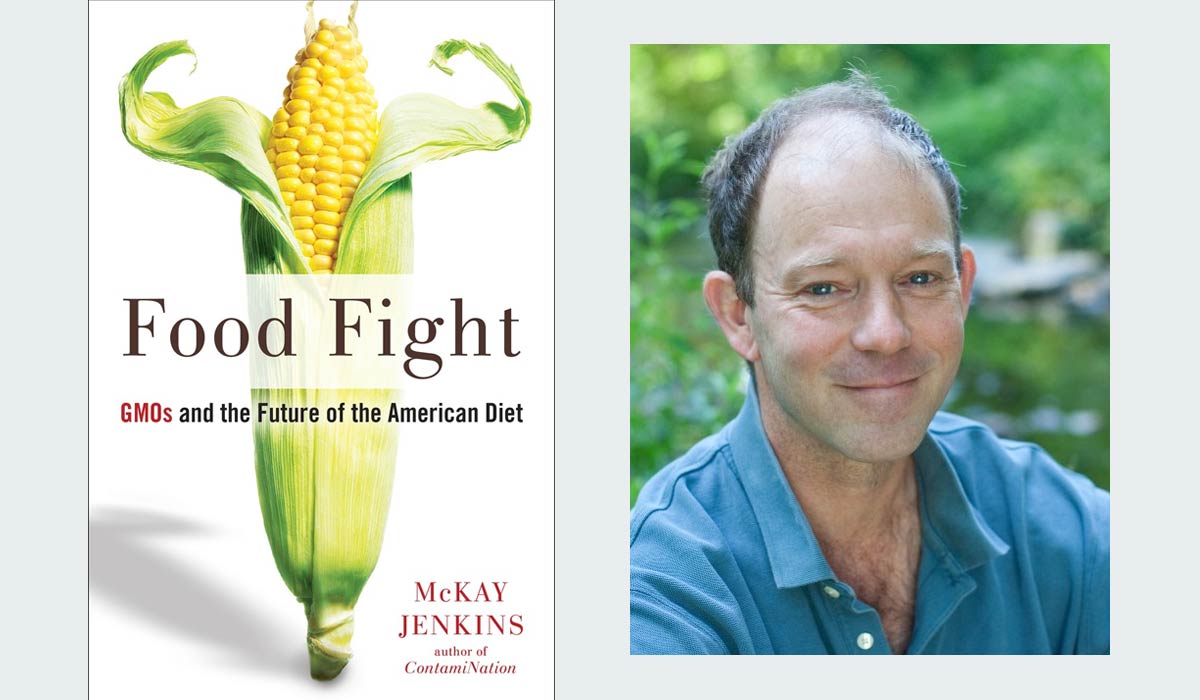

McKay Jenkins, who has written several books about environmentally related topics, is author of the new book, Food Fight: GMOs and the Future of the American Diet. Jenkins traveled throughout the U.S. interviewing scientists, farmers, and activists to get their perspectives on genetically modified farming and food.

Unlike many GMO books that are written from a pro- or anti-GMO stance, Jenkins takes a more nuanced approach. As a journalist, Jenkins tries to bring a balanced perspective to the GMO debate, saying the issue is not “black and white but complicated and worth having a pretty long conversation about.”

Jenkins is also Cornelius Tilghman Professor of English, Journalism, and Environmental Humanities at the University of Delaware.

Ken Roseboro, editor of The Organic & Non-GMO Report, interviewed Jenkins about Food Fight.

What led you to write Food Fight?

McKay Jenkins: I wrote another book called ContamiNation, which is about the presence of petrochemicals in consumer products, from drinking water bottles and carpeting to cosmetics and upholstery. Petrochemicals are building blocks of all these things, and that book is about the health and environmental consequences of using products that you can find by the untold millions in every big box store in the country.

It’s a first person account because I had a cancerous tumor and was asked about any chemical exposure I had. I investigated that and went down the rabbit hole looking at all those consumer products.

The idea for Food Fight came out of this investigation, and I decided to dive into the food question and how industrial food makes its way from the industrial farm to the supermarket. When you start looking at that you immediately come across the GMO debate, which to me is just part of a much larger conversation about industrial food production and how the American diet has been built on that.

My purpose with the book was to get people to think more deeply about food and their choices about the way they eat because each choice they make, scaled up, turns into a global food system.

What were some of the most interesting findings in your research for the book?

Jenkins: In chapter two, I described the cultural context for how this phenomenon of GMOs came to be. The construction of the interstate highway system was key to all this because building highways and suburbs essentially paved over four million small family farms. Food production moved to the Midwest, and it became efficient to grow food in one part of the country and ship it to another part. That made monoculture crops the most efficient way to grow food.

Then I picked stories that got at this complexity. I went to Hawaii and did a chapter about the fight on Kauai about pesticides and GMOs. I went to Maui and did a chapter on how they are trying to ban GMOs and then went to the big island and wrote about the (GMO) ringspot resistant papaya, which many people don’t like but many others think it is a great example of the positive use of genetic technology.

I spent time at the Land Institute, a great research institute in Kansas where they are using traditional breeding to create grains that can be grown as perennial polyculture (multiple) crops that can replace monoculture annual crops, which are creating such an environmental problem.

I did everything I could to dig into as many little pockets of complexity as possible to make this issue come alive.

How did it affect your perspectives on GMOs?

Jenkins: I started out thinking that GMOs are part of this industrial food system, which I’m very skeptical about. But then I interviewed a lot of scientists who I came to admire and who say that they are doing publically funded genetic engineering research in order to solve some challenging problems. They would talk about creating crops that might be useful in an era of climate change or adding nutrients to undernourished cultures. Those scientists had a non-corporate goal that might be in service of something I think we can all agree on: that the current state of agriculture is radically unsustainable.

I heard pretty convincing arguments that the technology could be used in a way that could be beneficial. I’m not saying that it is in any way being used that way. I’m saying there are credible, well-intentioned scientists doing some really exciting work.

There are people who disagree with that and are dead set against using GMOs even if they contribute to sustainability. I let them have their say too.

What do you see as the negatives of GMOs?

Jenkins: The vast majority of genetic engineering is now being used to further an industrial food system that is damaging to our health, environment, biodiversity, climate, and everything else.

Wes Jackson (founder of the Land Institute) gave me a paper that describes problems in agriculture from 1990 and problems in agriculture in 2015. The list is the same with soil loss and degradation, water pollution, monoculture, genetic erosion, factory farms, and toxic chemicals. The two lists are exactly the same except that in 2015 GMOs are on the list.

Jackson believes that GMOs are a distraction from a larger problem, which is that we have up to 300 hundred million acres of three monoculture crops—corn, soybeans, and wheat. That is a gargantuan environmental and health problem. And when you add the GMO part it becomes even more complicated.

John Vandermeer, Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Michigan, says that “genetic engineering is based on dramatically incomplete knowledge of the genome.” Did any of the scientists you spoke with address that issue?

Jenkins: I think he said that the genome is like an ecosystem. If you monkey around with one thing, you have no idea how it will percolate through the system.

But I talked to other scientists who don’t think the genome is like an ecosystem. This is where you get these scientists arguing with each other. Do you think the genome itself is something you can manipulate in a controlled way or do you think the genome is like an ecosystem that is subtle and interconnected in unimaginable ways that you can’t possibly predict what will happen if you mess around with one thing or another?

As a non-scientist, given what I know about other ecosystems, I intuitively think that is a good metaphor. You drop a pebble in a pond, it ripples out, and you don’t know what is going to happen. So it seems to me that if it’s true in system after system after system, it is probably true with genetics as well. But I’m the furthest thing from a geneticist.

Proponents of industrial agriculture say organic farming can’t feed the world. What are your thoughts on that?

Jenkins: That’s a complicated question. I’m not entirely sure that studies bear out the lower yields of organics. If you listen to the Rodale Institute, over time, organic yields are as good as non-organic.

When you talk about feeding the world; feeding them what exactly? Do you want to feed the world cheap hamburgers and potato chips? We are certainly good at that but that’s not what the goal should be.

This whole feeding the world thing is really much more complicated and interesting. Industry wants a short answer to that, they want you to think they can do it, end of story. But that is disingenuous.

What did you learn about creating a more sustainable food system?

Jenkins: Wes Jackson says that seventy percent of calories come from grain; you can have all the organic tomatoes in the world but you’re not going to feed anybody. You need grain. His solution of perennial polycultures could be a big part of this. So lots and lots of small farms producing lots of diverse crops are needed in addition to a different kind of grain production.

I end the book with profiles of local farmers and talk about my own efforts to bring my college students out to farms. They realized how difficult and honorable it is to be a farmer and learned that maybe they should spend money to buy food from people who grow food in their own communities. The effort is to get them to take responsibility in their part of this conversation even to the point of growing food themselves or getting to know people who grow it.