Scientist: Genetic engineering has become a religion

By Ken Roseboro

Published: October 31, 2013

Category: GMO Environmental Risks

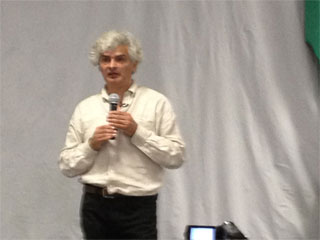

Ignacio Chapela

To access all the articles in this month's issue of The Organic & Non-GMO Report, SUBSCRIBE NOW.

Ignacio Chapela says people must challenge the false “stories” of genetic engineering

Genetic engineering has become an ideology similar to a religion, says Ignacio Chapela, a microbial ecologist at the University of California at Berkeley. Speaking at the recent National Heirloom Seed Expo, Chapela compared the science of engineering to the Catholic Church, which he said has beautiful stories. “I was raised Catholic, and the religion has survived for so long because of its stories,” he said.

GMO scientists are like priests

Now genetic engineers are telling us stories, for example how GM foods will help feed the world. “GMOs are no different from that (the church). Scientists are like priests. This is being pushed as an ideology,” Chapela said.

Chapela said the ideology of genetic engineering has been built on a wrong scientific paradigm, the “central dogma,” which states that specific traits are predetermined by genes.

Initially, he said scientists were excited about the possibility of “mixing and matching” traits in different species. “Some said let’s find the genes for wings and put them in pigs so they could fly,” he said.

But the scientists weren’t able to work such miracles because their theory was wrong, and Chapela started to doubt the science behind genetic engineering.

“The whole foundation of genetics turns out to be wrong,” he said. “Eye color is not determined by a single gene. DNA is not a master molecule. We have the benefit of 40 years (of GMOs failing) and should liberate ourselves from the central dogma. How many (GMO) traits have they developed? Two after 40 years.”

"Edifice of genetic engineering is mud on the ground”

Instead of DNA being a master molecule that determines a person’s traits or likelihood to get certain diseases, Chapela believes the environment plays a bigger role. As an example he cited a 2004 study in Sweden that found that a grandfather’s diet when he was young influenced his grandson’s likelihood to get some diseases more than the genes he passed on.

“What I become wasn’t in my grandparents’ DNA, it came from the environment. If that single story is true, the whole edifice of genetic engineering is mud on the ground,” he said.

Chapela has been a long-time critic of genetic engineering. In 2001, he and fellow researcher David Quist published a paper in Nature describing how genetically modified corn had contaminated native corn varieties in Oaxaca, a remote area of Mexico. Pro-GMO scientists and supporters attacked the study, but Chapela’s findings were later confirmed by a study published in 2009. Chapela has also been an outspoken critic of UC-Berkeley’s ties to biotechnology companies and was nearly denied tenure because of his stance.

Students told “Thou shalt not ask any further”

The fact that the central dogma is wrong is not publicized. “You don’t hear much about it,” Chapela said. “The reporters don’t write about it.”

Instead he says researchers are told: “Thou shalt not ask any further. This is what we are teaching students today.”

Further, he said genetic engineering became a technology to make money for biotechnology companies, which he said “should be remembered as some of the worst actors in history.”

Despite being based on an obsolete paradigm, genetic engineering continues to be pushed by a political agenda. “The policy (of the US government) has been to remove limitations to biotech,” he said.

Chapela said the “story” of GM “golden rice” continues to told again and again. “We dealt with that 10 years ago and to go back and deal with it again is boring,” he said.

Chapela emphasized the need to break out of the stories of genetic engineering’s wonders and to challenge the scientists who promote them. “Challenging their stories is very important,” he says.

Instead of a dogma, Chapela sees “another world” of complexity in biology. “The world is so much more exciting,” he said. “People who look at biology more closely see that. It’s become an open field.”

There needs to be a holistic perspective to agriculture, which is badly missing with genetic engineering. “The knowledge that a farmer has is as important as the soil, and seeds can’t be seen in isolation,” Chapela said.

© Copyright The Organic & Non-GMO Report, October 2013